ABOUT THE AUD 1933 KIMBALL PIPE ORGAN

HISTORY • SPECS • AUDIO RECORDINGS • PHOTO GALLERY

WORC ORGANS • MUNICIPAL ORGANS • FUN FACTS

Curator – Will Sherwood, AAGO, ChM, WorcAGO Dean 2010-2018

Resource Links:

October 2016 Organ Festival Week Concerts Press Release (PDF)

2016 Festival Concert Details/Bios/Programs

Worcester War Memorial Auditorium (AUD)

Lincoln Square, Worcester MA

W. W. Kimball Company

W. W. Kimball Company

Chicago IL, Opus 7119, 1933 EP

Organ Historical Society Plaque given 1983

1933 Kimball $40K Contract & Original Specs

Interesting Competitive Specs Proposal by Aeolian-Skinner

AUD Specs Request (RFQ)

Live for Today, Preserve for Tomorrow

Major Organ Recitals Through the Years:

- 1933 Palmer Christian

- 1955(?) & 1957 Virgil Fox – T&G Reviews (that fateful generator power supply!)

- 1956 E Power Biggs

- 1983, 1987 Earl Miller

- 1984 Gillian Weir (last organ recital for 30 years)

- 2016 William Ness, Peter Krasinski, Peter Richard Conte

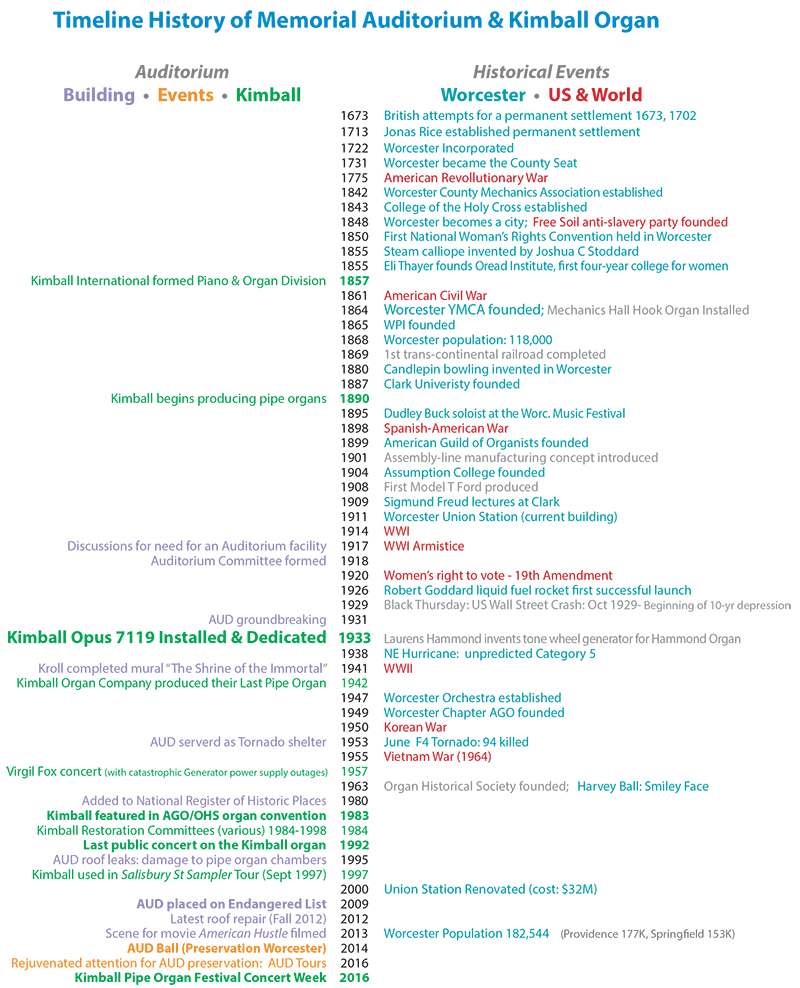

ORGAN HISTORY

The elegant Art-Deco building, designed by Lucius Biggs of Worcester and Frederic C. Hirons of New York, cost $2,000,000 and was opened in 1933, in “memory of those who died in the war.” The auditorium originally seated 4,500; the (original) stage accommodated a chorus of 500; and the elevating orchestra pit provided space for 100 musicians. (There are no chairs currently in the Great Hall main floor, and its balconies are off-limits.)

After the economic boom of the 1920s, organ building fell on hard times: Hook & Hastings (the successor to E & GG Hook, builder of The Worcester Organ at Mechanics Hall) folded in 1935; Skinner closed its Westfield MA branch in 1929 and absorbed the defunct Aeolian Organ Company in 1932 (to become Aeolian-Skinner). By 1933, Kimball was deeply in the red and there was talk of closing. Instead, they downsized their operation, and concentrated more on pianos, while still building an occasional organ until 1942. The AUD instrument was built in their last decade, one of the last large instruments they produced.

In spite of the economy and business conditions, Kimball came through with extraordinary quality in craftsmanship and musical results. The magnificent AUD organ was designed by Walter Howe, official organist, assistant director, and manager of the Worcester Music Festival; head of music at Abbot Academy, Andover; organist at First Baptist Church, Arlington, Mass.; and choral director at Chautauqua, New York; he was assisted in the planning process by R. P. Elliot, the New York representative of the Kimball Company; Hamilton B. Wood, president of the Worcester Festival Association; and Aldus C. Higgins, a member of the organ committee, who had a large concert organ in his home (Aeolian Op. 1686, 1928, 3-30, later moved to St. Joseph’s Abbey, Spencer).

In an advertisement in The Diapason magazine, 1 November 1933, the W. W. Kimball Co. waxed eloquent about the new organ:

Against the background of a classical Open-Great ensemble is placed a wealth of soft effects and orchestral color. The Great Diapasons and their complementary upperwork are of pure tin, resulting in an harmonic quality of tone, the chief attributes of which are perfect blending and crystalline clarity. Low and moderate pressures have been used throughout except for the Tubas and Bombardes. Tonally, it represents sane ideas in designing and voicing which, while rooted in the best traditions of the past, are advanced and modern in every respect, yet far from radical. The tonal effects of this splendid organ will delight and interest both the organist and the layman.

The drawknob 4-manual console is set on its own elevator, independent of the elevating orchestra pit. There is a “filler” cage/platform which currently sits on the stage (holding up the many-ton stage firewall “curtain”) which was used to “cover” the organ console such that when the console elevator was lowered to the appropriate height, the upper surface of this cage provided a continuous floor to match the orchestra pit elevator floor level, for when the organ was not in use. Additionally there is a wooden stair and gang plank of sorts in the basement where the organist would (almost) crawl onto the organ bench when awaiting ascension by the elevator to be lifted up for an eager audience. This mini-stair and platform is adjacent to a wiring and wind hose supply catch basin “reservoir” of sorts to manage the console’s tethered range of motion.

Organ chamber wind pressures range from 5 inches through 6, 7 to 8, 10, 12, 15 to 17 or 20 inches [of water].

28 “inches of water” (which is more than the above Kimball pressures used) equals 1 PSI which also equals 0.07 Atmosphere (i.e., less than 1/10th of the air pressure we breathe). Yet witness a major wind leak or take a pipe out of its pipe chest hole and the rush of air can be greater than a common house fan on high speed.

“Inches of water” is a common unit of measure for pipe organs as well as HVAC furnace blower pressures. It is common because it’s easy to measure: fill a U-shaped clear tube (hose) with water (called a “manometer”), and blow slightly into one end and measure (in inches) the difference in the two water levels.

The 74th Worcester Festival took place in October 1933 and for the first time utilized the Memorial Auditorium, previous events having been held at Mechanics Hall, home of “The Worcester Organ” (the 1864 Hook). The Verdi “Requiem” was the principal offering on the opening night, October 2, with more than 4000 people in attendance; another highlight of the evening was the playing of “Dedicace,” a sonata in one movement by Walter Howe, written especially [composition date is earlier though] for the new Kimball organ. The week before the festival week, a “civic evening” program was given with a chorus of 1,102 voices, made up of more than 60 choirs of Worcester, supplemented by an orchestra of 88 players, made up of the two symphony orchestras of the city. The climax of the evening was the singing of “Land of Hope and Glory” to the music of Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance” March.

The formal opening recital on the organ was presented November 6, 1933 by Palmer Christian of the University of Michigan. His program included: Toccata in C Major, Bach; Prelude from the Ninth Sonata for Violin, Corelli; Minuet and Gigue en Rondeau, Rameau; Fantasia and Fugne in C Minor, Bach; Sonata Eroica, Jongen; Benediction and Chorale Improvisation on “In dulci Jubilo”, Karg-Eiert; Pantomime, Jepson; Prelude on an ancient Flemish Melody, Gilson; Scherzo, Rousseau; Prelude to ‘The Blessed Dainosel”, Debussy; Nocture, Grieg-Christian; and Carillon-Sortie, Mulet.

(Most of the foregoing information is quoted or adapted from articles in The Diapason, 1 April 1933 and 1 November 1933.)

Unlike most large and important concert organs in the United States (and elsewhere), this instrument has never been altered in any way. It is exactly as it was when it was installed, except for dust (budgetary constraints will require private donations to accomplish a much-needed cleaning … )

The Memorial Auditorium organ, though neglected for years, fortunately has not gone to ruin. Partly because it was neglected, it has survived for a long time, because no one cared enough about it to bother trying to alter it. It has survived, too, because it was beautifully made. It represents a style of organbuilding, and manifests a quality of construction, that we are not likely ever to see again. It is our great good fortune that it is intact. Funding for restoration could the Kimball organ to once again take its rightful place as “The Other Worcester Organ.”

Additional Review & Commentary from Larry Chace & Grahame Davis:

The 1933, 107-rank Kimball organ which is in the War Memorial Auditorium at Worcester, Mass. is surely one of Kimball’s finest instruments. It resembles the 1938 instrument which Kimball built for the Episcopal Cathedral in Denver, Colorado. The Worcester Kimball is larger and is not as buried as the Cathedral organ. Ten years ago, I and some other builders were privileged to be able to spend many hours touring through the organ, taking scales and measurements and examining other details. At the time, my firm was about to begin the restoration of 1928 Kimball (four manuals, 58 ranks, now[1997] complete), and we wanted to see along what lines the company developed its later, and subsequently final, tonal philosophy. Tom Murray from Yale ably demonstrated the organ to us, and we all quite pleased to note that only one drawknob refused to cancel [still in early 2016], there being a blown console pneumatic….this after no maintenance for at least ten years. How’s that for good, solid American organ building?! All of the builders present were stunned by the beauty of the individual voices, the cohesiveness of the ensembles and the regulation and balance of the entire instrument….still intact and working well 53 [1997] years later. This instrument was built during the last days of Robert Pier Elliot’s reign, and I commend to all a study of this man’s influence on several organ companies of the day. His story may be found in David Junchen’s Encyclopedia of the Theater Organ, under the listing ‘beautifully made’. All the Kimball voices speak promptly and are very effective in the room.

The Kimball is an example of R. P. Elliot’s conception of a “classical” instrument, and it is well-supplied with a tin Diapason chorus on the Great consisting of 16,8,8,8,8,5-1/3,4,4,3?,2,V,VI with chorus reeds of 16,8,8,4. The Pedal has a 32’ wooden Violone, a 32’ Major Bass (stopped wood), and a 32’ Bombarde of metal. (The Great’s 32’ is a tenor-C Gemshorn, also playing at 16’ and 8’.) There are additional mixtures in the Swell (V), Choir (III), and Pedal (V). The Pedal has its own unenclosed 16’ Open Diapasons one wood and a separate one metal as well as a further enclosed 16’ open wood.

The Swell also has a chorus of 16,8,8,4’ Trumpets. The Choir’s is only 8,4, as are the Solo Tubas. (All are independent.) The Pedal 32’ Bombarde, unenclosed, also plays at 16,8,4, while its enclosed Trombone plays at 16,8,4.

(Larry Chace, Grahame Davis on PIPorg-L 1997)

Commentary

We in the 21st Century are accustomed to being tuned in to music through all types of media and sources. However, in the 1920s and 30s, even though the phonograph (gramophone) had been invented in 1877, it was not in common usage (the first jukebox was produced only in 1946). Live music was often the only source of listening pleasure, from the common home piano or pump (reed) organ to small jazz bands to symphony orchestras in concert halls.

In the late 19th century, the pipe organ began to grow beyond its traditional liturgical role into something more: Live music was the main source of music to be heard, and the widespread availability of organs (in churches, concert halls, theaters, and residences) along with the broad gamut of repertoire possible (from compositions written for the organ to orchestral transcriptions and extemporaneous improvisations that dazzled audiences) was the perfect combination for the rise of the pipe organ as a concert instrument. Orchestras were expensive to staff and maintain, and travel was much more difficult, thus the organ (with a single player) became an effective substitute.

Organbuilders jumped at the chance to create instruments that could rival symphony orchestras in power and color, and the rise of the Symphonic Organ in the early 1900s reached its zenith in the booming 1920s. Theater organs, which had their own style of organbuilding, sprang up simultaneously to accompany silent films. Eventually, organbuilders offered differing capabilities for each instrument, based on the intended usage, and the “American Classic Organ” emerged to be able to play most repertoire from Baroque to Romantic and Contemporary periods.

Celebrating the King of Instruments

At its earliest origins, from the days of the humble pan flute to the mighty hydraulis that filled the Roman coliseums with massive sounds, the pipe organ has been an instrument of curiosity and wonder. It has inspired many throughout the ages, including the great master Johann Sebastian Bach, who toured his native Germany to test various organs’ “lung power” with his prodigious keyboard technique. A contemporary virtuoso, Cameron Carpenter, draws crowds in the thousands to hear him play this amazing instrument, as did recitalists of yesteryear such as Virgil Fox or E Power Biggs. Worcester has enjoyed its share of fine organists throughout the years, concertizing locally as well as on tour internationally.

The most common use for the organ is in churches. Why is that, especially considering the negative connotation of its early usage at gladiator fights which persecuted religious followers? In some ways it is an obvious transition – the vast cathedrals were similarly large spaces to fill with grand music. Another reason is not so obvious, and yet we experience it even today: No instrument encourages singing better than the pipe organ. As an organist makes thousands of pipes sound at once in hymn playing, the instrument mimics the exact same physics of the human voice – an air column in a tube is set into vibration. This vibration is contagious, such that when we all sing with the organ supporting us, we are literally vibrating together!

The W. W. Kimball Company

Wallace W. Kimball (1828-1904), a native of Rumford, Maine, settled in Chicago Illinois, in 1857, as a buyer and seller of pianos. In 1880, he started building reed organs (by 1922, when his firm phased out that part of its operation, it had produced 403,390 of them) and branched out into piano manufacturing in 1887. In 1890, in association with a young Englishman, Frederick W. Hedgeland, W. W. Kimball Co. introduced a line of portable pipe organs; these cleverly designed instruments were compact, simple to prepare for moving, and fairly easily moved. In 1894, the firm commenced building “stationary” organs. By 1942, when the organ factory was closed, W. W. Kimball Co. had built 7,326 pipe organs, among them some of the largest and most important of their time. Notable among these were four-manual instruments for the Cathedral of St. John-in-the-Wilderness, Denver, Colorado; the. Municipal Auditorium in Minneapolis; the Municipal Auditorium in Memphis; First Baptist Church in Los Angeles; and a five-manual organ for the Roxy Theater in New York City. The Chicago factory, “Kimball Hall” was located on Wabash Avenue, near Jackson Street; the firm maintained a New York City office at 665 Fifth Avenue for many years.